Landowners in the United States spent just under $800 million in 2014 and 2015 on title insurance, according to the American Land Title Association. Americans are unusual in the world in this respect. Our system requires the parties involved in a real estate transaction bear the risk for verifying that properties involved have a clear title. That’s why people here buy title insurance. If there’s a dispute, the policies cover any loss.

In most other developed economies, the state takes on this cost for all property (which means all taxpayers share the price of keeping an official registry), so there is no market for title insurance. In many less developed parts of the world, there isn’t much of a system for handling property at all. It leads to disputes, fraud and slower than necessary economic growth. That said, much like places that didn’t have wired telephone systems and leapfrogged to mobile, these places may have a chance to leapfrog the developed world’s old fashioned databases to a more secure, distributed system and on to a better economy.

The Observer has found three projects on three different continents where entrepreneurs and changemakers have experimented with putting land titles onto the blockchain. An immutable record of titles on a blockchain has certain advantages over a paper system or even a digital database held on a secure cloud. Fraud and abuse by government officials tends to cause people to distrust title systems in less developed countries. If titles were logged on a blockchain, every single little change to a record would be logged on the public database. Officials would not be able to tamper with a record without leaving a digital trail that anyone could easily follow.

Ghana

Governments have been slowly digitizing property records for a while now, Emmanuel Noah, CEO of Ghanian startup BenBen told the Observer during an interview at the United Nations. “What happens most of the time when they digitize records is they scan them and put them on a hard drive,” he said. In Ghana, BenBen is building a solution that turns those records into real data, where every single field on a record makes it searchable, sortable and opens the property records up to real analysis.

We met Noah and BenBen’s COO, Daniel Bloch, at the 2016 Solutions Summit, where global startups came to pitch new ventures whose works help advance the global body’s sustainable development goals.

In their presentation at the event, the pair showed a photo of a house with the words “this house is not for sale” spray painted on it. They said that this is a common way for homeowners to show that a place is occupied and that opportunists should not try taking it from them. “People sell land they don’t have,” he told the crowd.

Land is a financial source, he explained. If people can prove they own it, they can borrow against it. With borrowing, they can start businesses and grow the local economy. Currently, Ghana’s economy has a $38 billion economy with 27.4 million people, according to the World Bank. Giving it slightly more people than Texas (the second most populous state), and an economy the size of Wyoming’s (the second smallest, by GDP).

The platform is not yet wedded to a specific blockchain. “We want to make sure what we’re building is super secure and proven,” Bloch said. “Ethereum is really something we’re keen on due to the aspect of smart contracts.”

In other parts of the world, a similar venture would have to overcome laws written for yesterday’s best practices for managing information. “In Ghana, precedents have not been set,” Bloch said.

BenBen completed an accelerator run by Barclay’s and Techstars in July. It was just shortlisted for the Thomson Reuters Africa Startups Challenge.

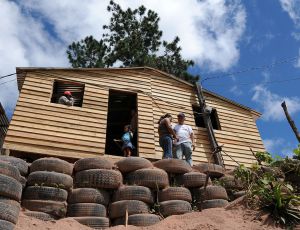

Honduras

Last year Factom announced a similar initiative in Honduras. In a blog post in May 2015, the company wrote:

By building an immutable title record, backed by blockchain, Honduras can leapfrog systems built in the developed world, [Factom President Peter] Kirby said. He added that this would allow for more secure mortgages, contracts, and mineral rights.

“This also gives owners of the nearly 60 percent of undocumented land, an incentive to register their property officially.”

Factom has built a platform that makes it possible to store an enormous amount of data on the bitcoin blockchain. It basically creates hashes of data that correspond to larger records. Several of these hashes can be stored in one bitcoin transaction, as Bitcoin Vox explains. As the largest, most distributed blockchain, the bitcoin chain is the most secure, providing landowners with considerably more peace of mind.

In a blog post from Christmas 2015, Factom announced that the project in Honduras had stalled due to political roadblocks. Factom partnered on the project with Epigraph, a land title company. Officials from Honduras have repeatedly refused to comment on the project to reporters, as CoinDesk reported.

Honduras’s economy sits at about $20 billion, with 8 million people, according to the World Bank (much smaller than that of Vermont, the smallest economy in the U.S., but its population is roughly the size of the 12th most populous state, Virginia).

Republic of Georgia

A contributor to Forbes posted a story about bitcoin miner and infrastructure company Bitfury‘s new pilot program in Georgia. The company intends to build a permissioned blockchain, controlled by the Georgian government, but secured by the bitcoin blockchain, according to CoinDesk.

Forbes quoted BitFury CEO Valery Vavilov saying:

“Why the blockchain? It will help do three major things,” he said. “First, it will add security to the data so the data cannot be corrupted. Second, by powering the registry with the blockchain, the public auditor will also make a real-time audit. So the auditor will audit the registry not once per year, but every 10 minutes [for example]. Third, it will reduce the friction in registration and the cost of property rights registration, because people could do this in the future using their smart phones. Blockchain will be used as a notary service.”

In September 2015, BitFury announced its intention to build a 100MW data center outside Tblisi.

Georgia’s economy is $14 billion, with a population of 3.8 million, according to the World Bank (less than half the size of Vermont’s), making it the smallest economy in this roundup. Its population is roughly the size of Oklahoma, nearly at the median of U.S. states.

None of these projects are anywhere close to what could be described as real yet, but they are all also ventures in what is, for many parts of the world, a commercial and political greenfield. BenBen’s Bloch said, “We want to influence policy.”