It’s been said the beginning of Kosmische Musik—the hypnotic, minimalist style of music crudely dubbed “Krautrock” by the British press in the late ’60s—lies in the wake of World War II. The trance-like atmosphere and sterilized rhythms were the result of a sound designed to mirror the shell shock that fell over Germany after the demise of the Third Reich as well as the Schlager pop music deemed appropriate for public consumption by the government.

“There were not too many ways for a German rock musician to perform music, to make music, even to think of the theoretical development of music because there was no heritage in the country,” explains the late Edgar Froese of the groundbreaking electronic outfit Tangerine Dream in the BBC documentary Krautrock: The Rebirth of Germany.

“And the Germans were in a very bad situation. You couldn’t forget that. I mean, they were so stupid and guilty for it, to start two wars. As horrific as it was it had one, forgive me to say that, one positive point. There was nothing else to lose. They lost everything. And so, when we thought about doing music in a different form, there was only the free form, the abstract form.”

Oddly enough, when David Bowie began exploring this new music coming out of Germany from groups like Tangerine Dream and Cluster and Kraftwerk, he was coming under fire for some of the things he was saying while under his Thin White Duke persona in 1976.

He called Adolf Hitler one of the first rock stars in Playboy and dropped this gem during an interview with the NME: “Britain is ready for a fascist leader…I think Britain could benefit from a fascist leader. After all, fascism is really nationalism…I believe very strongly in fascism, people have always responded with greater efficiency under a regimental leadership.”

The backlash to what Bowie had called “two or three glib theatrical observations on English society” prompted him to declare “I am NOT a fascist.”

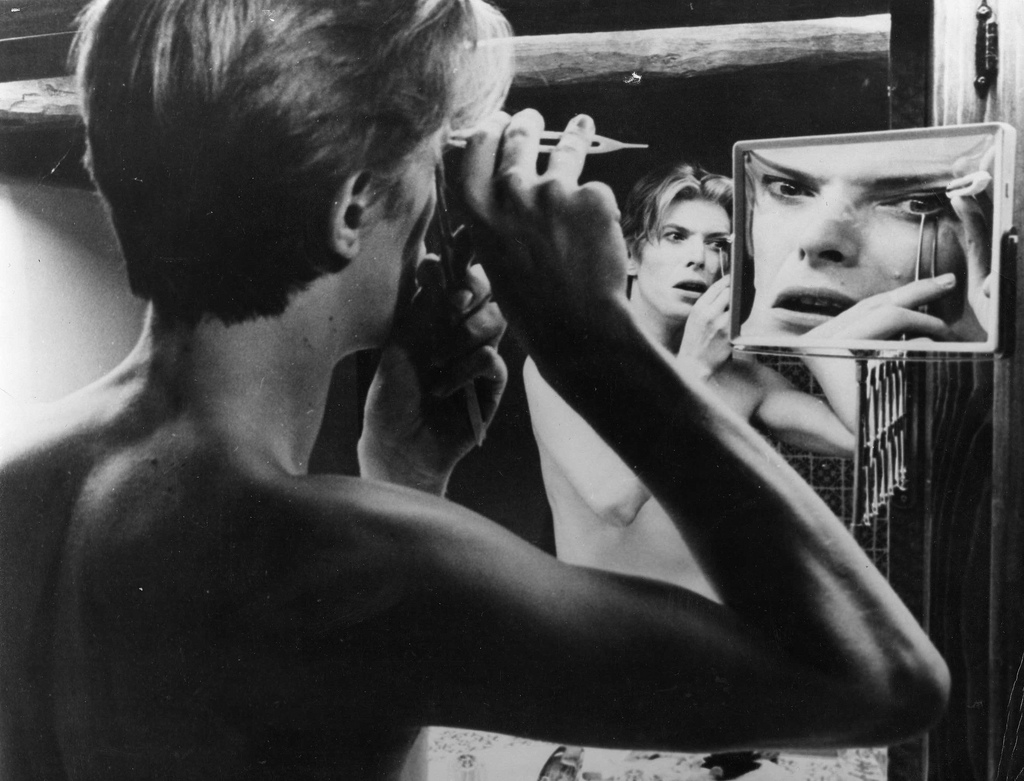

Yet this new form of music that emerged from West Berlin and Cologne in the late ’60s and early ’70s saved Bowie from nearly losing everything by the end of ’76—a year as disastrous for the singer in terms of his rampant dependence on cocaine as it was momentous for the release of his transitional masterpiece Station to Station and its subsequent tour, producing Iggy Pop’s classic solo debut The Idiot and landing himself a starring role in Nicolas Roeg’s sci-fi drama The Man Who Fell To Earth.

“I was in serious public decline, emotionally and socially,” Bowie told The Telegraph in 1996. “I think I was very much on course to be another rock casualty. In fact, I’m quite certain I wouldn’t have survived the ’70s if I’d carried on doing what I was doing. But I was lucky enough to know somewhere within me that I was really killing myself, and I had to do something drastic to pull myself out of that.”

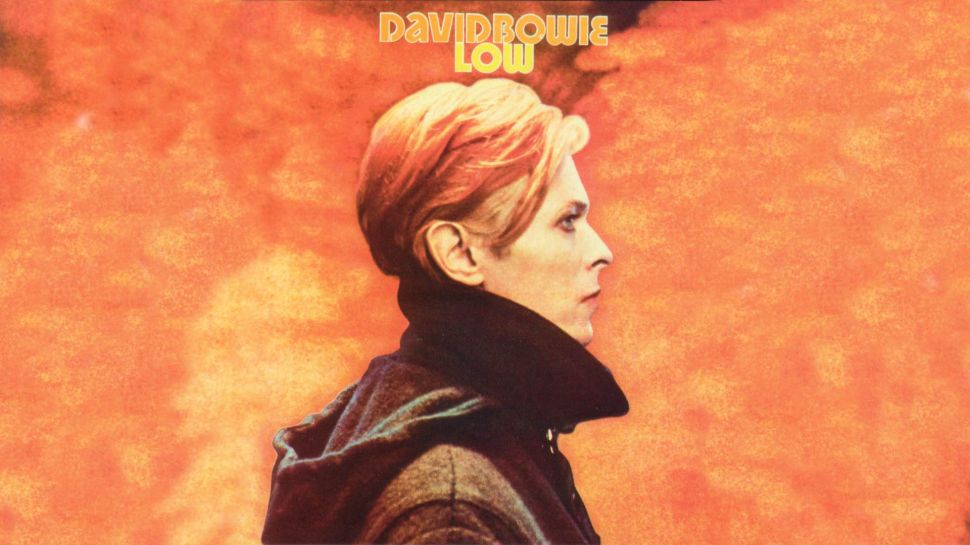

He started looking to the sterility of German Kosmische Musik for that emotional and artistic reboot when he began work on his next album, Low, the first installment of Bowie’s celebrated “Berlin” trilogy (which also included his other 1977 full-length Heroes and 1979’s Lodger). In fact, the music for Low actually took root two years prior when Bowie began composing music in hopes of seeing it used for the soundtrack to The Man Who Fell to Earth.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OTegaun_SDc?list=PLJNbijG2M7Ozs7jVSayh4XsS6p-Hc6KK_&w=560&h=315]

“Various Low tracks were reported to have been recycled from this time,” reveals author Hugo Wilcken in his 33 1/3 book on the album. “Brian Eno said that ‘Weeping Wall’ started life there although Bowie claims that ‘the only hold-over from the proposed soundtrack that I actually used was they reverse bass part in “Subterraneans.” ’ These sessions’ real contribution to Low was that they got Bowie thinking about (and creating) atmospheric ‘mood’ music for the first time.”

It was during those initial (and still unreleased) sessions with Space Oddity producer Paul Buckmaster that the Duke began taking a vested interest in the music of Kraftwerk, particularly their then-newly released LP Radio-Activity—the album’s balance of experimentalism and repetition provided the seeds for what would become Low.

“What I was passionate about in relation to Kraftwerk was their singular determination to stand apart from the stereotypical American chord sequences and their wholehearted embrace of a European sensibility displayed through their music,” Bowie explained to Uncut in 2001. “One had the feeling that Florian and Ralf were completely in charge of their environment, and their compositions were well prepared and honed before entering the studio. My work tended to expressionist mood pieces, the protagonist (myself) abandoning himself from the zeitgeist with little or no control over his life.”

To assist him in his vision, Bowie reached out to fellow English avant-glam weirdo Brian Eno to help him navigate the foreign waters of modern music.

“I knew he liked Another Green World a lot,” Eno told The Guardian’s Michael Watts in 1999. “And he must have realized that there were these two parallel streams of working going on in what I was doing, and when you find someone with the same problems you tend to become more friendly with them.”

But it was clear that the former Roxy Music keyboardist’s ambient oeuvre was the factor that directly drew Bowie to Eno as a creative partner for his next endeavor.

“He said when he first heard Discreet Music he could imagine in the future that you would go into the supermarket and there would be a rack of ‘ambience’ records, all in very similar covers,” Eno told Watts in that 1999 interview. “They would have titles like Sparkling or Nostalgic or Melancholy or Somber. They would be mood titles and so very cheap to buy you could chuck them away when you didn’t want them anymore.”

Despite Bowie’s intentions before recording Low, the union he established with Eno produced something far more than disposable supermarket music. What the duo created in this first installment of the Berlin trilogy was a collection of songs that perfectly bridged the gap between the funky plastic soul maneuvers of Station to Station on side 1 and his new station as brave explorer of the Motorik Autobahn on the flip, forming two distinctive halves that transformed into a seamless work.

“Both sides glisten with ideas,” proclaims Rob Sheffield writing about Low in his latest book On Bowie.

“Listening to Low, you hear Kraftwerk and Neu!, maybe some Ramones, loads of Abba and disco. But Low flows together into a lyrical, hallucinatory, miraculously beautiful whole, the music of an overstimulated mind in an exhausted body, as rock’s prettiest sex vampire sashays through some serious psychic wreckage.”

“It’s my reaction to certain places,” Bowie himself explained to Tim Lott of The Record Mirror in 1977. ” ‘Warszawa’ is about Warsaw and the very bleak atmosphere I got from that city. ‘Art Decade’ is West Berlin—a city cut off from its world, art and culture, dying with no hope of retribution. ‘Weeping Wall’ is about the Berlin Wall—the misery of it. And ‘Subterraneans’ is about the people that got caught in East Berlin after the separation—hence the faint jazz saxophones’ representing the memory of what it was.”

While the likes of guitarist Carlos Alomar, bassist George Murray, keyboardist Ray Young and percussionist Dennis Davis among others graced these recording sessions, it was the Ziggy-Eno dream team that did most of the heavy lifting on Low, especially on its instrumental second side.

“I became the sculptor to David’s tendency to paint,” Eno said to MOJO in 2007. “I keep trying to cut things back, strip them into something tense and taut, and he keeps throwing new colors on the canvas. It’s a good duet.”

The most common misconception of Eno’s role on Low was that he played a part in the album’s production; that credit belongs to Bowie’s most trusted sonic compatriot Tony Visconti, a man who not only helmed the entire Berlin trilogy but Bowie’s final four studio albums as well, including 2002’s excellent Heathen and, of course, 2016’s masterful last goodbye ★.

“Over the years, not enough credit has gone to Tony Visconti on those particular albums,” Bowie said in 2000 of Low, Heroes and Lodger. “The actual sound and texture, the feel of everything from the drums to the way my voice is recorded—it’s Tony Visconti.”

It was also what Visconti brought to the sessions that helped make Low one of the most distinctive titles in the Bowie canon.

“They asked me what sonically I could bring to the table,” Visconti explained to Sheffield for On Bowie. “And I told them about this new gadget I had bought, the Eventide Harmonizer. They asked what it did and I said, ‘It fucks with the fabric of time.’ ”

Forty years later, Low continues to do just that—formulating something both distinctively in time with the bleeding edge of 1977 yet layered with such forward-thinking artfulness it still cannot be properly matched in 2017. Low is an album that will make you dance, think and weep all in the span of 38 minutes and 26 seconds as Bowie seeks salvation in a form of music too futuristic for even Thomas Jerome Newton himself despite the character’s appearance on its cover art.

“Overall I get a sense of real optimism through the veils of despair from Low,” Bowie declared in that 1999 interview with Uncut. “I can hear myself struggling to get well.”

“I think all my art is based on living, not on doing art; in experiencing life in many, many different aspects. The young part of the Hitler Youth, it was called ‘Pimpfen.’ They tried to make us soldiers, but fortunately the war ended in the right time.”